Moving a glacier in sixteen parts: lessons from GreenerU’s own strategic plan process (Part I of II)

Strategic plans do a great job of helping organizations gain alignment and focus on common outcomes. But one of the trickiest parts about developing a plan is actually implementing it. Here at GreenerU, we put ourselves to the test. This is Part I of a two-part article.

Strategic plans come in many different shapes and sizes. And they’re critical. Strategic planning gets diverse individuals to a common focus to align intentions and work toward a common set of goals.

If they’re developed well, they’ve been structured to gather input from a diverse group of representative individuals who have insight and buy-in from people who will ultimately have to carry out the plan. Without that buy-in, a plan might prove to be confusing, burdensome, or just plain useless.

But here’s what they don’t tell you in strategic plan school: creating a plan is only one step of the process. One of the trickiest parts about developing a plan is actually implementing it. Here at GreenerU, we have put ourselves to the test.

Developing the vision

As has happened for many of our clients—including ECU (East Carolina University), Concord Academy, University at Albany, Mount Holyoke College, and others—GreenerU came to the conclusion that we would do better, more effective, more efficient work if we created a strategic plan.

Developing a long-range vision was the first step. That was created by our four-person management team, in conjunction with our board of directors, who wanted to see GreenerU hit a series of targets that ultimately strengthen our ability to carry out our mission: helping schools mitigate climate change.

This alone was challenging. It’s so much easier to think tactically—to come up with ideas to put out the day-to-day, month-to-month operational fires. But the key to visionary thinking is imagining what success looks like; to invest time in thinking about what the organization could and should look like much further down the road.

When visioning, I always like to think of Don LaFontaine, the serious-voiced movie trailer guy, taking us to an alternate reality: “In a world…” And that’s what we have to do when we’re thinking about the long-term. We have to get big and bold—we have to paint a portrait of something different than the world we already know.

For GreenerU, our futuristic 2029 world looks like one where we’re serving a broader base of clients, where we’re more agile and adaptive, and where we are thriving financially. In short, our vision is to be strong, stable, and rooted in our core values so that we’re poised to do our best work. Check. How that translated into a three-year strategic plan was a lengthy next step.

Creating the plan: the investigation phase

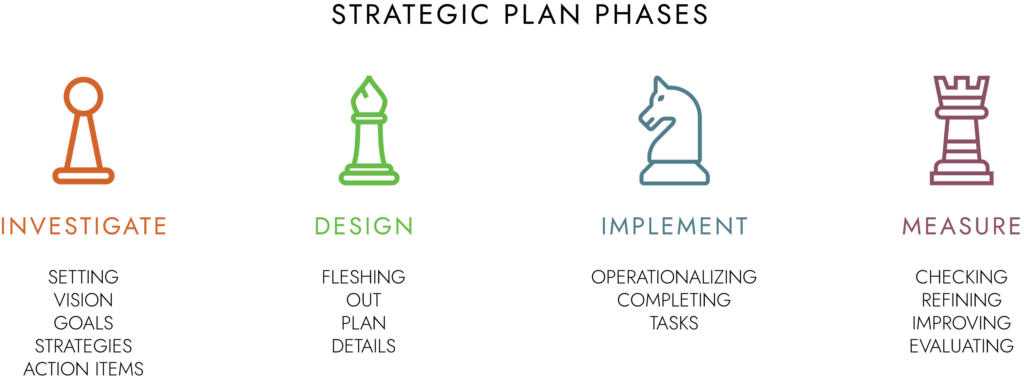

There is more to developing a strategic plan than getting people into a room. It’s a multi-phasic process that only begins with developing a plan. Using the same model as we approach our turnkey energy construction projects—investigate, design, implement, measure—I’m calling the planning phase “investigate.”

To begin with, we did a deep-dive investigation through the plan creation phase. As a firm with a robust consulting arm, we were awfully lucky to have in-house expertise and support to guide us through this phase.

I say this because this part of the process is a bit of a roller coaster. Idea generation is exciting. Knowing you need to reduce that list of ideas developed by impassioned employees is the equivalent of the slow tick, tick, tick of the ride before you nosedive into spirals, twirls, and a dark tunnel of divergent opinions. Human beings are loss averse and this phase can be incredibly challenging, which is why Community at Work dubbed it the “groan zone.”

And we groaned a lot.

For those who aren’t aware, GreenerU has two different business lines: turnkey energy solutions and change management. This means our employees range from the highly technically driven to the highly relationship-driven. No one would accuse GreenerU employees of being shrinking violets.

There is a reason why roller coasters have harnesses. Likewise, there is a reason why we have structure and process to our strategic planning. Both are to ensure no one gets flung off during the twists and turns of the ride. And meeting core values, such as honesty and openness and full participation, ensure that no limbs are lost in the process.

If you’ve ever participated in our Facilitation for Organizational Change workshop or read Sam Kaner’s excellent Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, you’ll be familiar with what happens when a group of people start confronting change.

The reason for strategic planning is typically that business as usual isn’t getting you where you were hoping to go. And then you start talking about those plans: new ideas start proliferating, disagreements and differences of opinion surge, the possibilities and limitations seem like a gaping abyss, a wave of anxiety sets in, and it feels like a genie you can’t put back in the bottle.

Creating a set of goals, even with a rock-star in-house facilitator, took us the bulk of a year. We had three working groups: business development, culture, and process. Each of these working groups was tasked with creating short-term, three-year goals and accompanying strategies that would ultimately be the building blocks toward achieving the 2029 vision.

Finally, in early 2019, a staff-driven plan had been run up the flagpole to the management team, which made a series of tweaks and final recommendations. We polished it up in a final document that detailed what we hoped to accomplish by 2021: a set of nine goals, 16 supporting strategies, and dozens of tactics.

All set, right? Oh no.

Fleshing out the plan: the design phase

As much as we seemed to have accomplished by the time the plan launched, another challenging phase of hard work was about to begin: the design phase.

Many of these strategies have broad-brush directives: “grow company service territory” and “develop project finance offerings” and “create a project completion document” and “create an intentional hiring and onboarding process,” etc.

Zero of these strategies are simple. They all require clarification, agreement on the ultimate deliverables, research, discussion, management team members’ buy-in, more discussion, cost-benefit analyses, and ultimately approval before we can even begin to implement any of the recommendations.

In creating a plan—but especially in implementing a plan—it is important to embrace ambiguity. You don’t know what you don’t know. It is, after all, your best attempt at following a road map into the future. And there will be unexpected barriers along the way.

It’s natural that you won’t accomplish everything you set out to do. In fact, it would be irresponsible to try to do so. So you’ll want to be adaptive to new information or new opportunities. But you will certainly move important initiatives forward that used to be trapped in the “you know what we should do?” talk of yesteryear.

In Roger Martin and A.G. Lafley’s book, Playing to Win, embracing the unknown is broken down into these three concepts:

- Strategy is about making choices. To win, a company must choose to do some things and not others.

- Strategy is about increasing the odds of success. There is no such thing as a perfect strategy.

- Successful strategy-making combines rigor and creativity. Strategy should be creative and scientific—it involves generating and testing hypotheses.

Of course, too much ambiguity can lead to despondence. More on that in Part II.

Having been through the highs and lows of the multiple phases of strategic planning has helped us gain even greater insight into how to help your institution craft its visions, goals, and strategies thoughtfully. We want you to benefit from what we’ve found! Talk to Us and let’s start a conversation.