Finding the light: a case for investments in improved lighting schemes in schools

As we continue to march through the 21st century, schools are increasingly turning an eye on being greener and saving green.

Consider the ubiquity of lighting in how we function every day.

Human essentials are often categorized as food, shelter, and clothing, but I would go even further and include clean air and water—and maybe jazz, but that’s just me.

And I would definitely include light.

As we continue to march into the 21st century, schools are increasingly turning an eye on being greener and saving green. This essay outlines the importance of getting lighting just right in classrooms, laboratories, sports facilities, and other campus spaces for the best learning outcomes and the unique opportunity presented by revolutionary changes in lighting technology to leverage energy savings to pay for dramatic improvements in the quality of your buildings’ visual environment.

Lighting and the brain

“Light is the most important environmental input, after food and water, in controlling bodily functions.”

This quote by Dr. Richard Wurtman, a neuroscientist and physician who spent about six decades splitting his time between Harvard and MIT, pretty much sums up the importance of why schools should pay close attention to lighting in academic environments.

In fact, there’s been a growing body of research in the past ten years about how physical space affects learning. Kenneth Tanner, a professor at the University of Georgia College of Education, has done extensive research on how physical environments influence behavior and productivity. He’s also looking at student productivity in “green” schools.

Fluorescent lamps, which are about as ubiquitous as light itself, have been a mainstay in classrooms, warehouses, office buildings, and factories since they came on the market almost eight decades ago. They are cheap, bright, and use less energy than incandescent bulbs, which accounts for their widespread use over the years.

Unfortunately, fluorescent lighting has presented a whole host of problems. Consumers have never liked the buzzing, flickering, color rendering, and lag time of fluorescent lighting systems. Even when fluorescent lamps are working properly, they come with underlying hazards: research has shown that some forms of fluorescent lighting may affect some students and teachers by causing mild seizures. Older types of fluorescent lighting can create an imperceptible flicker, which contributes to visual problems (tracking, refractive errors, strabismus). And visual problems, such as tracking difficulty, can lead to behavioral and learning problems.

Lighting and the wallet

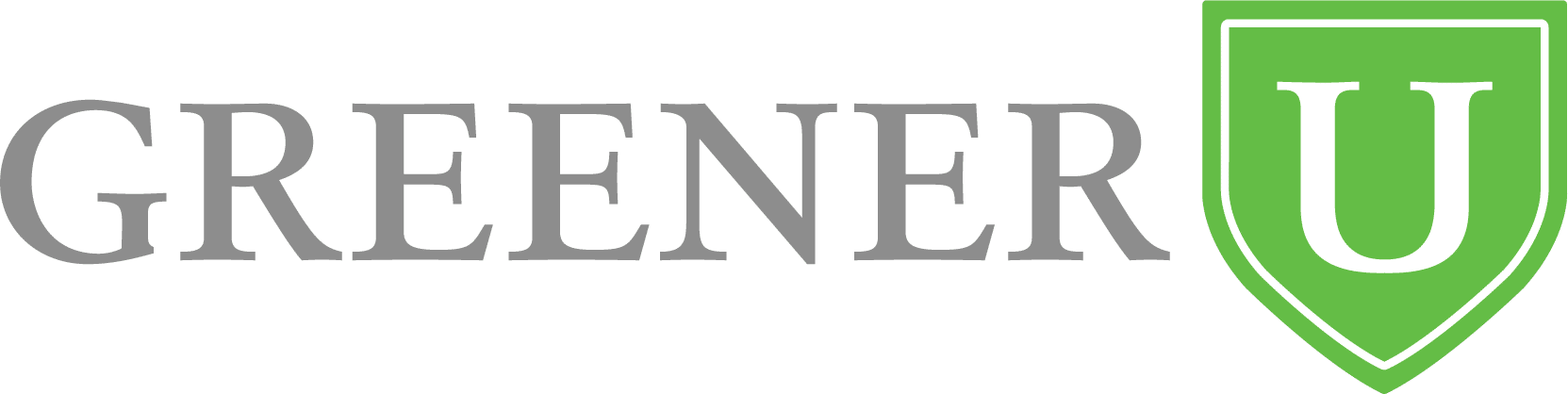

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, on average, 31% of college and university energy use is on lighting (see Figure 1). That’s even more energy than is spent on ventilation (22%) or cooling (20%).

As most facilities professionals will tell you, managing energy consumption is one of the most effective ways of reducing costs, and they achieve this through more efficient and smarter HVAC systems, appliances, lighting systems, and better integration of controls.

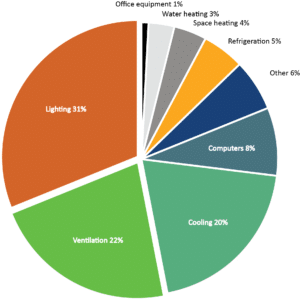

When it comes to gaining efficiencies in lighting, nothing has been more revolutionary than the emergence of light-emitting diode (LED) bulbs. This technology has been around for decades, but only very recently became commercially viable, and even more recently started to come down in cost. LED lights have several magical qualities: they burn brighter than incandescents on far less energy, they are highly dimmable, and they come in multiple shapes and sizes.

Meanwhile, costs have come down very dramatically in the last decade. Those cost reductions have started leveling off and are likely to continue slowly, but nowhere near the dramatic decreases we’ve seen recently (see Figure 2).

Herein lies the big opportunity: with LED systems now significantly more efficient than the best fluorescent systems out there and available at reasonable prices, there is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to use the significant energy savings from upgrading to LEDs to pay for completely new lighting systems—which can be redesigned to best serve the needs of the spaces they’ll be lighting well into the 21st century.

In short, you’re presented now with an opportunity to reduce energy consumption in lighting systems by 50–70% at costs that are dramatically lower than they were even two or three years ago.

Energy-efficient light bulbs are only one part of what will ultimately deliver the biggest financial savings on college campuses. With the ability to integrate control of lighting systems with HVAC and other building systems, this opens another realm of energy- and cost-saving opportunities.

So even if you simply replaced your existing fluorescent tubes with LEDs, you miss out on a major opportunity to integrate that lighting with a network of systems that have far more sophistication than “on” and “off.” This has the added benefit of extending the life of the LED equipment, further enhancing the maintenance benefits associated with the long service life of LEDs.

What’s more, utility incentives, especially in New England, have really sweetened the deal. In the Boston area, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA) has invested almost $6 million in energy-efficiency upgrades, including lighting, in its Angell Medical Center, which leveraged about $400,000 in utility incentives from the local electricity provider, Eversource.

Lighting in the 21st century

Knowing all the above—that outdated lighting impacts learning environments, and it also can be one of the largest energy vampires on campuses—why are so many classrooms outfitted with lighting schemes from the 1950s?

Now is a great time for colleges to take the great leap forward on classrooms with beautiful, functional, energy-efficient lighting that can improve students’ learning environment. In fact, many colleges we’ve worked with have made giant strides toward ushering in 21st-century lighting by integrating their set-up with building automation systems. This means they can easily tweak their lighting output, use motion sensors to determine when a building is in use (or not), and automatically activate or deactivate climate control settings as well.

Case in point: Brown University hired GreenerU to update the lighting in its Pizzitola Indoor Tennis Facility. Built in 1989, Pizzitola’s existing lighting was using 581,612 kWh of power each year. At Rhode Island’s above-average commercial electricity rates, that meant Brown was spending more than $80,000 on electricity for lighting in Pizzitola alone.

GreenerU worked very closely with Brown not only to redesign the lighting for energy savings, but for aesthetics and performance as well. Our lighting specialist spent a lot of time iterating and reiterating to ensure the lighting levels were just right.

After the redesign, Pizzitola’s lighting only used 265,790 kWh, a savings of 315,683 kWh, or 54%. Lighting controls added another 93,690 kWh in savings. With both lighting redesign and integration with the building automation system, Pizzitola now has a 70% decrease in lighting energy use.

While these photographs don’t do it justice (Figure 3), it’s a lot easier to see the ball on these tennis courts now.

Conclusion

There’s never been a better time to upgrade lighting on campuses than right now. Learning and development research supports it. Costs of efficient lighting materials are lower. Building automation systems make everything work together smoothly and efficiently. And overall, campuses are looking at a multitude of solutions toward lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

Especially important to consider is the opportunity these cost savings present to campuses to provide a shot in the arm of funding to improve on lighting schemes, making spaces more appropriately lit for the activities that take place in them. If colleges simply plug new bulbs into old fixtures, they walk away from their best chance to make dramatic improvements to their lighting schemes.

Light is an essential ingredient in this recipe for 21st-century academic success and the ways schools hope to prepare students for the future. Let’s get it right.

—David Adamian is CEO of GreenerU, Inc., based in Watertown, Mass. His Billboard Top 100 hit, “Blinded by the Light,” was stolen and subsequently recorded in 1973 by Bruce Springsteen, who never amounted to much of anything important.

Figure 1. — Electricity use in U.S. colleges and universities.

Figure 2. — Cost-to-efficacy comparison of LED bulbs.

Figure 3. — Pizzitola Indoor Tennis Facility at Brown University: before and after lighting redesign and installation.

References:

Wurtman, R.J. (1975). The effects of light on the human body. Scientific American, 233, 68-77.

Tanner, C.K. (2008). Explaining relationships among student outcomes and the school’s physical environment. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19, 444–471.

U.S. Department of Energy. (2015). Quadrennial Technology Review: An Assessment of Energy Technologies and Research Opportunities. From https://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/03/f34/quadrennial-technology-review-2015_1.pdf.